Unlikely Neighbors?

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer, 6/3/2025

Nature Corner: Part 1: Rocking Robins On Both Sides of the Ocean

By: Wendy Oellers-Fulmer

Our beloved and ubiquitous American Robin has a counterpart in Europe, the European Robin.

Beloved in England and Ireland, these songbirds share a similar appearance and behaviors, but are actually different species. The American Robin belongs to the Thrush family, stocky birds with large eyes; while the European Robin belongs to the Old World Flycatcher family who are specialized to catch insects in flight.

Both songbirds primarily eat insects, earthworms, spiders and small invertebrates during the late spring through fall. During the winter, they rely on seeds and berries. They both have vibrantly colored breast feathers, while the European Robin has a bright orange face, shorter “bib” and brownish back, the American Robin’s face matches its grayish back. The American Robin is also larger, 8 1/2-11 inches compared to the 5 1/2-inches of the diminutive European Robin.

Our American Robin got its name from European settlers, who were delighted to see the familiar vibrant coloring of their beloved “Robin”.

Pink Lady Slippers – New Hampshire’s State Wildflower

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer, 05/27/2025

Nature Corner: Pink Lady Slippers – New Hampshire’s State Wildflower

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer

On a walk this week, I was delighted to discover a group of our New Hampshire state’s beautiful wildflower, Pink Lady’s Slippers (Cypripedium acaule Ait.)

This once prolific wildflower, a member of the orchid family, has seen a significant decline due to human development including agriculture, urban development and road construction. The more common Pink Lady’s Slipper is actually listed as a “special concern: under the Native Plant Protection Act.

Lady’s Slippers can live for many years if left alone. But they require a specific climate and soil conditions to grow and propagate. Like other orchids, they require a specific fungus in the dirt to germinate and grow. While other plants have food inside their seeds, they need the fungi to break open the seeds and attach to them. Once attached, the fungi flows both food and nutrients into the seeds, causing it to germinate and grow.

It can take from 10 to 16 years before the plant first blooms, but these wildflowers can survive for over 20 years. Lady’s Slippers do not transplant well due to their particular environmental needs for survival. To protect these beautiful flowers, we need to observe them in their wild places and let them bloom undisturbed.

To discover more:

Dandelions – Protect for the Pollinators or Poison

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer, 05/20/2025

To

Nature Corner: Dandelions – Protect for the Pollinators or Poison

By: Wendy Oellers-Fulmer

Bright yellow dandelions are one of the earliest flowering plants, bringing vibrant pops of color to our lawns and countryside. Dandelions are critical plants this early in the year for over 100 species of insects; and the leaves and seeds feed over 30 species of wildlife including birds. The flowers attract pollinators, like bees, butterflies, and moths which in turn pollinate flowers, fruits, herbs, and vegetables that feed even more species.

Dandelions, which are herbs with many valuable uses, can be appreciated or denigrated, by well-meaning homeowners, wishful for a smooth, weed free green lawn. But dandelions, when treated with weed killing poison controls and pesticides, can be a danger to key species in our ecosystem. In particular, the pesticide glyphosate has proven to have serious repercussions on wild bee colonies and other animals.

If you need to remove dandelions, the safest way to do this is pull them out by their roots. There are many tools on the market that help you achieve this. You can also use neem oil, vinegar, and/or epsom salts to prevent the devastating harm that poisons can do to our ecosystems.

To learn more:

Glyphosate Weedkiller Damages Wild Bee Colonies, Study Reveals

The Healing Power of Nature

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer, 5/13/2025

Nature Corner: The Healing Power of Nature

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer

There is a powerful antidote to the maladies of anxiety and stress produced by over exposure to the technology-driven world. We can simply shut it off and spend some time in nature. In a busy life, deliberately choosing to spend time in nature can seem like one more demand. But multiple studies have shown there is a direct correlation between spending time in nature and improvements in mood, mental heath and emotional well-being.

In fact one study showed that spending time in nature can calm and regulate our nervous system in less than five minutes! It doesn’t seem to matter what age this powerful antidote can impact. Children who spend quality time in nature have improved academic achievement, higher self-esteem and creativity.

What are some ways to bring nature back into your busy, modern day life? Opening your senses to the beauty and wonder of the natural world is the first way. It focuses your attention on the present moment, pulling you out of the rabbit holes of worrying about the future. It can be as simple as gazing in awe at the vibrant vista of a sunset, reveling in the sound of waves crashing on a beach, savoring the delicate scent of a flower, tasting freshly picked berries, and/or tracing the softness of a feather.

Bringing our attention and appreciation to the gifts that surround us in the natural world, can help the over-stimulated mind. You can even bring nature indoors, with artwork, plants, and sound recordings of natural phenomena.

So in this blooming time of year, gift yourself the gift of the healing power of nature.

The Journey of A Thousand Miles Begins with a Single Flap

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer, 5/6/2025

Nature Corner: The Journey of a Thousand Miles Begins with a Single Flap

by Wendy Oellers-Fulmer

The Chinese philosopher, Lao Tau, has been attributed with the quote “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step”, signifying that even the most major of undertakings begin with a single action.

In the Avian world, some birds have huge “undertakings” as they migrate back and forth between time here in the spring and summer during the breeding season, and down south during the winter.

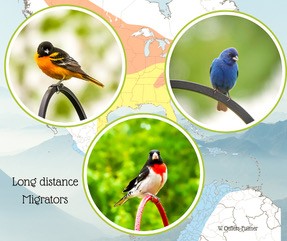

Three long-distance migrators arrived back in our yard in the last two days: Baltimore Orioles, Indigo Buntings and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks.

Considering the fact of the uncertainties that migrating birds face, (habitat loss, light pollution, obstacles and barriers, bad weather, and predators), it’s amazing that they survive the arduous journeys.

All three of these persevering birds travel over a thousand miles in the Spring and Fall. The Rose-breasted grosbeak flies all the way to Central and Northern South America. The vibrantly blue Indigo Bunting can travel 1,200 miles each way to winter in southern Florida and northern South America. The Baltimore Oriole travels to wintering grounds in Florida, the Caribbean, Central America, and the northern tip of South America.

To discover more about these beautiful birds: